Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Saturday, June 27, 2020

Further News and Updates

Because apparently I left stuff out of the last one.

--

1. The annual War for Darwin’s Basement is in full swing here in Our Little Town, as guys named Lefty and Claw hold their yearly contest to see who can be the first to burn down their garage with fireworks. On the one hand this happens – as noted – every year, so we’re used to it. It starts around Father’s Day and runs through mid-July, with the high point being Independence Day when they try to outdo the official city fireworks and the whole town ends up shrouded in a cordite haze. On the other hand, this year has been excessive even by the standards of people who think the secret to a good time is gunpowder and light beer. They don’t even wait for the sun to go down, which seems a waste since you can’t see the fireworks in broad daylight. On the third hand (hey – I’m an academic; I have an infinite supply of hands) some of these firework displays have been pretty impressive.

I’ve heard the conspiracy theories about the intensity of the booms this year, my favorite being that this is some kind of sinister effort to desensitize us to gunfire in the streets so we won’t notice the oncoming civil war. Dude, this is America. Gunfire in the streets doesn’t faze anyone here. I think we’re good on that score.

Mostly I suspect that after months of lockdown and with the official fireworks mostly canceled, people just want to blow shit up. MURCA!

2. So apparently in Britain the word “flapjack” does not refer to pancakes. Instead it refers to a sweet, chewy sort of oat and dried fruit bar. This came as a surprise to me. I’ve been following along this year with the acapella group Voces8, and since they can’t do concerts they’ve been doing all sorts of interesting livestream videos instead. It’s been a bright spot in an otherwise grim year. For a while they had the members share interesting recipes, and “Andrea’s Flapjacks” looked good so I tried them back in May. They did, in fact, rock. I made them again tonight and they were just as good. But I thought Andrea was being facetious with the name – that it was an analogy to pancakes, a claim that these were what pancakes ought to be, or something like that. Apparently not. This is what the British mean by flapjacks! No, no, no. That’s just wrong. Tasty, granted. But wrong.

3. In a better world Lauren would have come home from her year abroad last night and would be sleeping off some of the jet lag now. Sigh.

4. I have discovered how to stream Premier League games, now that they’re playing them again. For a sawbuck I got a subscription to the rest of the season – and with the streaming service you can watch replays whenever, so I can see games when I have time for them as long as I don’t go out of my way to find out the score ahead of time (and even if I do, they're still fun to watch). They offer two different versions – one with “natural sound” which means that’s its eerily quiet and one with “enhanced sound” where they pump in old crowd noise. I’ll take the latter, thanks. I miss crowds.

5. What do you think the odds are that der Sturmtrumper’s cultists will care that he has known for months that Russia has been paying bounties for dead American soldiers in Afghanistan and not only has he done nothing about it, he’s actually kissed up to Putin even further in that time? This is astonishingly criminal and he should be removed from office on a rail at the very least, but if events have shown us anything in this country it is that nothing matters more to the Trump cult than the Dear Leader – not morals, not laws, not preventable mass death from disease, not teargassing civilians, not putting children in cages, not anything – and I’ll put money on the fact that betraying American soldiers won’t matter either.

6. I suspect the military will remember it, though.

7. They keep telling us that Home Campus is going to have face-to-face classes in the fall, but nobody knows how that will actually work. A lot of colleges are pretty much in the same place right now. It’s not just us. On the one hand I don’t blame them for trying – they need a plan, if only to have something to deviate from. On the other hand, nothing anyone says before August 15 is going to mean anything, so hang onto your hats, folks.

8. I’m up to the newest Christopher Moore book now, and it’s kind of saddening to know that there won’t be another one after this, at least for a while (I mean, the guy is still writing after all, but the next one probably won’t be in stores for a couple of years). It’s been a fun ride.

9. I have a pile of boxes outside of my home office because at some point I am going to clean this room out and move some stuff on to the next happy home for it, but I’ve been saying that for over a year now and nothing has happened. Or, rather, everything else has happened. My classes end in August. Perhaps then.

10. It’s taken them three months, but the cats have finally figured out how to sleep with us home all the time and they’re not stumbling around like little furry zombies lashing their tails and demanding we get out and give them some peace anymore. So progress, really.

--

1. The annual War for Darwin’s Basement is in full swing here in Our Little Town, as guys named Lefty and Claw hold their yearly contest to see who can be the first to burn down their garage with fireworks. On the one hand this happens – as noted – every year, so we’re used to it. It starts around Father’s Day and runs through mid-July, with the high point being Independence Day when they try to outdo the official city fireworks and the whole town ends up shrouded in a cordite haze. On the other hand, this year has been excessive even by the standards of people who think the secret to a good time is gunpowder and light beer. They don’t even wait for the sun to go down, which seems a waste since you can’t see the fireworks in broad daylight. On the third hand (hey – I’m an academic; I have an infinite supply of hands) some of these firework displays have been pretty impressive.

I’ve heard the conspiracy theories about the intensity of the booms this year, my favorite being that this is some kind of sinister effort to desensitize us to gunfire in the streets so we won’t notice the oncoming civil war. Dude, this is America. Gunfire in the streets doesn’t faze anyone here. I think we’re good on that score.

Mostly I suspect that after months of lockdown and with the official fireworks mostly canceled, people just want to blow shit up. MURCA!

2. So apparently in Britain the word “flapjack” does not refer to pancakes. Instead it refers to a sweet, chewy sort of oat and dried fruit bar. This came as a surprise to me. I’ve been following along this year with the acapella group Voces8, and since they can’t do concerts they’ve been doing all sorts of interesting livestream videos instead. It’s been a bright spot in an otherwise grim year. For a while they had the members share interesting recipes, and “Andrea’s Flapjacks” looked good so I tried them back in May. They did, in fact, rock. I made them again tonight and they were just as good. But I thought Andrea was being facetious with the name – that it was an analogy to pancakes, a claim that these were what pancakes ought to be, or something like that. Apparently not. This is what the British mean by flapjacks! No, no, no. That’s just wrong. Tasty, granted. But wrong.

3. In a better world Lauren would have come home from her year abroad last night and would be sleeping off some of the jet lag now. Sigh.

4. I have discovered how to stream Premier League games, now that they’re playing them again. For a sawbuck I got a subscription to the rest of the season – and with the streaming service you can watch replays whenever, so I can see games when I have time for them as long as I don’t go out of my way to find out the score ahead of time (and even if I do, they're still fun to watch). They offer two different versions – one with “natural sound” which means that’s its eerily quiet and one with “enhanced sound” where they pump in old crowd noise. I’ll take the latter, thanks. I miss crowds.

5. What do you think the odds are that der Sturmtrumper’s cultists will care that he has known for months that Russia has been paying bounties for dead American soldiers in Afghanistan and not only has he done nothing about it, he’s actually kissed up to Putin even further in that time? This is astonishingly criminal and he should be removed from office on a rail at the very least, but if events have shown us anything in this country it is that nothing matters more to the Trump cult than the Dear Leader – not morals, not laws, not preventable mass death from disease, not teargassing civilians, not putting children in cages, not anything – and I’ll put money on the fact that betraying American soldiers won’t matter either.

6. I suspect the military will remember it, though.

7. They keep telling us that Home Campus is going to have face-to-face classes in the fall, but nobody knows how that will actually work. A lot of colleges are pretty much in the same place right now. It’s not just us. On the one hand I don’t blame them for trying – they need a plan, if only to have something to deviate from. On the other hand, nothing anyone says before August 15 is going to mean anything, so hang onto your hats, folks.

8. I’m up to the newest Christopher Moore book now, and it’s kind of saddening to know that there won’t be another one after this, at least for a while (I mean, the guy is still writing after all, but the next one probably won’t be in stores for a couple of years). It’s been a fun ride.

9. I have a pile of boxes outside of my home office because at some point I am going to clean this room out and move some stuff on to the next happy home for it, but I’ve been saying that for over a year now and nothing has happened. Or, rather, everything else has happened. My classes end in August. Perhaps then.

10. It’s taken them three months, but the cats have finally figured out how to sleep with us home all the time and they’re not stumbling around like little furry zombies lashing their tails and demanding we get out and give them some peace anymore. So progress, really.

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

News and Updates

1. We had a lovely Father’s Day here this past weekend. It was quiet, as they tend to be anyway even without the added incentive of a pandemic to keep us home. Both Kim and I are swamped this summer with classes, grading, and other assorted tasks (a nice problem to have in the current economy) and Lauren and Oliver are busy with other things as young adults tend to be, so mostly the four of us just had a very nice dinner and then played cards together. There were cards and some small presents, which I always appreciate, but really I got what I wanted when we sat down together at the table. There is nothing more precious in this world than time with my family, and I will savor every moment of it.

2. The atomic bomb class is back this summer, though for the first time in the 22 years we’ve been teaching it we’ve had to take it online. It’s been an experience. We’re doing the class by Zoom, since it’s much easier to do breakout rooms on that platform than on Webex (the platform that Home Campus uses) and to be honest I’m not really worried about the security or encryption of the class. What’s the worst that could happen? Someone gets educated?

3. I spent all last week grading AP exams. I was supposed to do that in Florida a couple of weeks ago, but instead I was at home, working around all of my various classes. I can’t say I’m unhappy about keeping my “never set foot in Florida” streak alive, especially now when that state has become one of the world’s leading exporters of Stupid here in the pandemic, but it is hard to focus on that kind of bulk grading at home. On the plus side, my roommate from last year’s AP (and this year’s had we gone to Florida) came by this weekend as he was in the area and we had a nice socially-distant visit in the back yard for a while. So win for us.

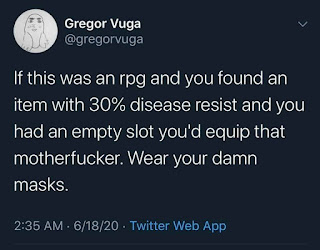

4. I’m mostly staying in these days, as I’ve done since March, because let’s just be honest here: the United States has utterly failed in its attempt to deal with the coronavirus. This failure starts at the top, with the catastrophically idiotic and gratuitously cruel response by der Sturmtrumper and his enablers, continues on down through every halfwit politician and Angry Armed White Boy complaining how masks and lockdown infringe on their right to infect other people, and ends with every maskless wonder at the beach or their church service waiting for the coroner to fit them for next month’s autopsy slab. No wonder the EU has pretty much banned all travel from the US. I’d ban us too. We are the laughing stock of the world right now, and I don't blame the world for that at all.

5. Just going to leave this right here. MURCA!

6. Naturally this is the time when our appliances have chosen to be problematic. The refrigerator is leaking water tonight – not a whole lot, just enough to warrant a call to the Appliance Guy, who knows us well by now. He’ll be by tomorrow. And while he’s here perhaps I’ll ask him about the dishwasher, which randomly seems to decide that it needs to go into Delay mode – sometimes while it’s washing things and sometimes not. The fridge is annoying since it’s not that old, but the dishwasher is Ollie’s age and it really doesn’t owe us anything at this point.

7. Just a reminder that there are still protests going on, that Black Lives Still Matter even if the right-wing extremists aren’t trying to frame the protesters for rioting as much anymore so it's not on the news every night, and that it’s long since past time that this country started treating its citizens as citizens and its non-citizens as human beings. Not sure what this says about the US that this needs to be repeated, but there you go.

8. Also, for those people out there who get hot and bothered by the fact that all those Confederate statues are coming down, get over it. Those statues should never have been put up in the first place and it is an unmitigated good that they’re being torn down and replaced by, well, anything. Or nothing. They should be melted down and made into something useful like ball bearings for roller skates.

We should not have statues of traitors or enemies. The Confederacy was a pretender nation founded on treason and dedicated to the preservation of human slavery. It declared war on the United States of America, killed hundreds of thousands of Americans, and was destroyed just as it deserved to be. The United States in particular and humanity in general were only improved by the annihilation of the Confederacy.

Statues do not exist to remember history. I’m a historian. We remember history just fine without statues. Statues exist to celebrate things. Statues of Confederates exist to celebrate treason and white supremacy. There is absolutely nothing about the Confederacy that any patriotic American should celebrate except its defeat and eradication. Topple the damned statues and melt them down and be done with them.

9. I spent an hour today trying to have a 15-minute doctor appointment by video, oh brave new world. It was nice to see the doctor and even nicer not to have some of the experiences that men of my age bracket invariably have at in-person check-ups, but I’m not convinced that healthcare by videochat is the best way to do this.

10. It’s hard to write about small things when the world is on fire, but sometimes you need a reminder that not everything has to be significant and that many of the things that make life worthwhile are not the things that are going to end up in someone’s history textbook. They’re important to me, and that’s what matters here.

2. The atomic bomb class is back this summer, though for the first time in the 22 years we’ve been teaching it we’ve had to take it online. It’s been an experience. We’re doing the class by Zoom, since it’s much easier to do breakout rooms on that platform than on Webex (the platform that Home Campus uses) and to be honest I’m not really worried about the security or encryption of the class. What’s the worst that could happen? Someone gets educated?

3. I spent all last week grading AP exams. I was supposed to do that in Florida a couple of weeks ago, but instead I was at home, working around all of my various classes. I can’t say I’m unhappy about keeping my “never set foot in Florida” streak alive, especially now when that state has become one of the world’s leading exporters of Stupid here in the pandemic, but it is hard to focus on that kind of bulk grading at home. On the plus side, my roommate from last year’s AP (and this year’s had we gone to Florida) came by this weekend as he was in the area and we had a nice socially-distant visit in the back yard for a while. So win for us.

4. I’m mostly staying in these days, as I’ve done since March, because let’s just be honest here: the United States has utterly failed in its attempt to deal with the coronavirus. This failure starts at the top, with the catastrophically idiotic and gratuitously cruel response by der Sturmtrumper and his enablers, continues on down through every halfwit politician and Angry Armed White Boy complaining how masks and lockdown infringe on their right to infect other people, and ends with every maskless wonder at the beach or their church service waiting for the coroner to fit them for next month’s autopsy slab. No wonder the EU has pretty much banned all travel from the US. I’d ban us too. We are the laughing stock of the world right now, and I don't blame the world for that at all.

5. Just going to leave this right here. MURCA!

6. Naturally this is the time when our appliances have chosen to be problematic. The refrigerator is leaking water tonight – not a whole lot, just enough to warrant a call to the Appliance Guy, who knows us well by now. He’ll be by tomorrow. And while he’s here perhaps I’ll ask him about the dishwasher, which randomly seems to decide that it needs to go into Delay mode – sometimes while it’s washing things and sometimes not. The fridge is annoying since it’s not that old, but the dishwasher is Ollie’s age and it really doesn’t owe us anything at this point.

7. Just a reminder that there are still protests going on, that Black Lives Still Matter even if the right-wing extremists aren’t trying to frame the protesters for rioting as much anymore so it's not on the news every night, and that it’s long since past time that this country started treating its citizens as citizens and its non-citizens as human beings. Not sure what this says about the US that this needs to be repeated, but there you go.

8. Also, for those people out there who get hot and bothered by the fact that all those Confederate statues are coming down, get over it. Those statues should never have been put up in the first place and it is an unmitigated good that they’re being torn down and replaced by, well, anything. Or nothing. They should be melted down and made into something useful like ball bearings for roller skates.

We should not have statues of traitors or enemies. The Confederacy was a pretender nation founded on treason and dedicated to the preservation of human slavery. It declared war on the United States of America, killed hundreds of thousands of Americans, and was destroyed just as it deserved to be. The United States in particular and humanity in general were only improved by the annihilation of the Confederacy.

Statues do not exist to remember history. I’m a historian. We remember history just fine without statues. Statues exist to celebrate things. Statues of Confederates exist to celebrate treason and white supremacy. There is absolutely nothing about the Confederacy that any patriotic American should celebrate except its defeat and eradication. Topple the damned statues and melt them down and be done with them.

9. I spent an hour today trying to have a 15-minute doctor appointment by video, oh brave new world. It was nice to see the doctor and even nicer not to have some of the experiences that men of my age bracket invariably have at in-person check-ups, but I’m not convinced that healthcare by videochat is the best way to do this.

10. It’s hard to write about small things when the world is on fire, but sometimes you need a reminder that not everything has to be significant and that many of the things that make life worthwhile are not the things that are going to end up in someone’s history textbook. They’re important to me, and that’s what matters here.

Friday, June 19, 2020

The Revenge of Nathaniel Bacon

Bacon’s Rebellion is the single most important event in all of American history, because pretty much everything that has happened since – and a good chunk of what you’re seeing in the headlines these days – can be traced back directly to what happened in Virginia in 1676. It sets American history in motion in ways that we’re still dealing with now, and if you want to understand this country’s history you need to understand Bacon’s Rebellion and its consequences.

Late seventeenth-century Virginia was a place ripe for conflict.

At first glance this might be surprising. The gruesome demographics of the earlier part of the 1600s had eased up a bit, and life expectancy had actually improved to the point where you weren’t taking a decade off of your life by emigrating there from England. Settlers going to the more northerly colonies in New England – where they didn’t build their main settlements in the middle of a swamp at just the point where the fresh water coming down the river became fouled by the seawater coming up with the tides – added a decade to their lives by heading for the New World, but Virginia had a well-earned reputation as a morgue in the first half century or so after the English colonized the place. By 1670 or so, this was no longer true.

And as late as 1650 the price of tobacco – the one crop that Virginians had managed to export in any significant amount – was still relatively high.

But beginning in the 1650s the price of tobacco began to fall, as Navigation Laws required all of the crop to be sent through England rather than directly to other markets and the iron law of supply and demand took its toll. By 1660 the price of tobacco had fallen to about a penny a pound – a third of what it was in 1650 and a thirty-sixth of what it was in 1620 when the tobacco boom started – and it would remain there into the 1700s. That’s below cost, which meant that it was economically impossible to make a living as a tobacco planter in Virginia in the late 1600s.

Unfortunately by 1660 tobacco had such a hold on Virginia that few men there could imagine making a living any other way, which meant that more and more Virginians tried to survive by growing a crop that earned them less and less money. There is no way that could end well. It’s just math.

The demographic improvements carried their own problems.

Slavery had been legal in Virginia from the very beginning, but from what historians have been able to piece together it was not all that common prior to 1660 and only slightly more common for a while after that. You do see evidence of enslaved Africans in Virginia as early as the 1640s and possibly sooner, but while bound labor was the only way that tobacco could be produced profitably this was overwhelmingly provided by indentured servants – usually English in the 1600s – rather than slaves.

Indentured servants are essentially temporary slaves. In exchange for passage across the ocean plus room and board they agree to serve as bound labor for a fixed period of time – seven years was common – during which time they could be bought, sold, and treated as things but after which they would be set free, given a reward (often land on the frontier), and allowed to join society as free citizens.

The first Africans in Virginia arrived in 1619 – a year before there were Pilgrims in New England, for those of you keeping score at home – and from what historians are able to tell they were treated as indentured servants as well – held in bondage, treated as things, and bought and sold like English indentured servants, but if they survived they were set free. There was in fact a small community of freed Africans in Virginia in the 1620s and 1630s, and they had the same rights as freed English indentured servants. They could own land and become tobacco planters. If they owned enough land they could vote and serve on juries – juries that were usually deciding the fates of white people, something that wouldn’t happen again in Virginia until the 1970s once the practice halted. They could marry who they chose, and even own indentured servants or slaves of their own.

This tells you that “race” as we understand the term didn’t mean a whole lot to the settlers. They were far more likely to care about religious views – there is a reason that Shakespeare’s Othello is described as the Moor (“the Muslim”) of Venice rather than the black man of Venice, after all.

That began to change in the 1640s, as “race” in the modern sense began to matter more to Virginians than it did in the decades prior. Historians are not exactly sure why this change happened but happen it did. You see laws passed discriminating between the rights of freed African indentured servants versus freed English indentured servants, denying freed Africans the right to serve in the militia or own a gun (gun ownership being a white privilege of long standing in this country). But slavery itself was still fairly uncommon and would remain so into the 1670s. In 1660 there were fewer than 1000 slaves in Virginia. In 1670 there were about 2000 – roughly 5% of the population. They were outnumbered by indentured servants three to one.

The reason for this is simple economics plus demographics. In the early 17th century few settlers, bound or free, survived seven years in Virginia. Slaves are expensive because you’re paying for a lifetime’s worth of labor, whereas indentured servants are far cheaper because you’re only paying for seven years’ worth of labor. And if both of them are likely to die before seven years is up, there’s no point in paying for a slave. You get all of the economic benefits of slavery without all the costs by going with indentured servants, and if you think it is immoral to reduce human beings to chattels this way you’re absolutely right. But that was the logic at the time. It wasn’t morality that kept slavery from being common. It was just finances.

But by the 1660s mortality rates had declined to the point where most indentured servants were surviving long enough to be set free. You’d think this was a good thing, and for the indentured servants it was, but it had consequences.

Those freed indentured servants would often be given land out in the back country, much to the dismay of the Native Americans who had already seen a large chunk of their land taken from them. This meant constant conflict between the settlers and the Natives, conflict that threatened to burst out into warfare at any time.

And having been tobacco field hands during their time in Virginia, those freed indentured servants would set about trying to make a living doing the one thing they knew how to do, which was grow more tobacco. Which means you had even more people growing a crop that was even less valuable, and you know what that means? It means they’re going to fail, that’s what it means.

So in the 1660s Virginia became divided into two hostile camps.

On the one hand you had the wealthy planter elites – the people who had made their money when tobacco prices where high and could now afford to branch out into other things like money lending or the fur trade. These people lived in the eastern tidewater areas and were the ones who controlled the Virginia government.

On the other hand, you had a growing number of small tobacco farmers out on the frontier – mostly freed indentured servants. These people were poor, powerless, and increasingly angry, particularly after the tidewater elite put strict property limits on their right to vote (voter suppression being an age-old tactic in the US) and refused to help them eradicate the local Native Americans, with whom the elites traded for their furs.

By the early 1670s Virginia was a society on the brink of disaster, and the guy who set things in motion was Nathaniel Bacon.

Bacon was 26 years old when he arrived in Virginia in 1674. Like many early Virginia settlers he was a gentleman – a social rank at the time, not simply a description of an adult male – and he was eager to rebuild the fortune he had squandered back in England. Governor William Berkeley was sufficiently impressed with the young man that he appointed Bacon to the governor’s council, but they very quickly fell out when Berkeley denied him a license to trade with the Natives.

Bacon then threw himself into the opposition – an opposition centered around the small tobacco planters of the back country – and became their leader.

After rising tensions turned to violence between the settlers and the Natives in 1675 and 1676 (largely because Bacon and the back countrymen worked on a “kill them all and let God sort them out” philosophy of deciding between allies and threats), Berkeley threw Bacon off the council entirely. Bacon then led the frontiersmen against the Virginia government, routed the colonial militia, and burned the capital, Jamestown, to the ground in the summer of 1676. Bacon then died of dysentery in October, after which Berkeley recaptured Jamestown, executed 23 of the surviving rebels, boarded a ship to explain the situation to the crown in 1677, and died before he could do so.

Given that I have just described the entire rebellion in a single paragraph of just over a hundred words – a rebellion which failed and left the original government in charge when all was said and done, it must be noted – it is a fair question at this point to ask how this could possibly be the most important event in American history.

The rebellion had consequences, that’s how.

When the tidewater elite looked back over the events of Bacon’s Rebellion, they asked themselves, “What was the main source of this revolt?” And the answer they came up with was obvious: the small tobacco planters out in the back country. Small planters who had once been indentured servants but had survived to earn their freedom and their land thanks to the declining mortality rates of 17th century Virginia. Bacon had led them, but they were the root of the problem and as long as there were indentured servants living long enough to be freed they would constitute a poor, angry, volatile underclass ready to be stirred up by an ambitious leader like Nathaniel Bacon.

But Virginia needed bound labor, because free labor wasn’t going to grow tobacco.

So the solution was clear: find a source of bound labor that they didn’t have to set free.

Slaves, in other words.

Slavery meant no dangerous class of poor, freed indentured servants to deal with, and thanks to the declining mortality rates and the fact that slavery was made inheritable through the mother (and think about the incentives in that little arrangement the next time someone tells you the free market is the engine of liberty, why don’t you) slavery was now not only cost effective but potentially profitable.

On top of that race-based chattel slavery created a bond between the eastern planter elite and the small western planters, one that would reduce future rebellions by keeping the two sides allied against a common enemy, because as long as you had race-based slavery whites would unite against blacks – even across political or economic lines, even at the expense of their own political or economic interests.

Convince poor whites that blacks or other non-whites are the enemy and they will slit their own throats every time. Go ahead and dispute that if you want. I dare you. Go ahead.

Bacon’s Rebellion is the single most important event in all of American history because more than any other event it sets the United States on the path toward race-based chattel slavery, toward dividing Americans into white and nonwhite, into people and things, and from that decision nearly all of the rest of American history flows.

By 1700 race-based chattel slavery is the default system of bound labor in the American colonies, particularly in the south. There were roughly nineteen thousand slaves in the Chesapeake region in 1700 – 22% of the population, more or less – which is a significant increase from 1670, and it would only continue to grow. By 1750 there were over 200,000 slaves in the thirteen colonies that would become the US. By 1775 that would be about half a million – again, roughly 20% of the population.

If you want to understand colonial society, you need to understand this. If you want to understand the Civil War, you need to understand this. If you want to understand pretty much any part of American history, you need to understand this.

If you want to understand the headlines today, you need to understand Bacon’s Rebellion and its consequences.

We’re living them now.

Late seventeenth-century Virginia was a place ripe for conflict.

At first glance this might be surprising. The gruesome demographics of the earlier part of the 1600s had eased up a bit, and life expectancy had actually improved to the point where you weren’t taking a decade off of your life by emigrating there from England. Settlers going to the more northerly colonies in New England – where they didn’t build their main settlements in the middle of a swamp at just the point where the fresh water coming down the river became fouled by the seawater coming up with the tides – added a decade to their lives by heading for the New World, but Virginia had a well-earned reputation as a morgue in the first half century or so after the English colonized the place. By 1670 or so, this was no longer true.

And as late as 1650 the price of tobacco – the one crop that Virginians had managed to export in any significant amount – was still relatively high.

But beginning in the 1650s the price of tobacco began to fall, as Navigation Laws required all of the crop to be sent through England rather than directly to other markets and the iron law of supply and demand took its toll. By 1660 the price of tobacco had fallen to about a penny a pound – a third of what it was in 1650 and a thirty-sixth of what it was in 1620 when the tobacco boom started – and it would remain there into the 1700s. That’s below cost, which meant that it was economically impossible to make a living as a tobacco planter in Virginia in the late 1600s.

Unfortunately by 1660 tobacco had such a hold on Virginia that few men there could imagine making a living any other way, which meant that more and more Virginians tried to survive by growing a crop that earned them less and less money. There is no way that could end well. It’s just math.

The demographic improvements carried their own problems.

Slavery had been legal in Virginia from the very beginning, but from what historians have been able to piece together it was not all that common prior to 1660 and only slightly more common for a while after that. You do see evidence of enslaved Africans in Virginia as early as the 1640s and possibly sooner, but while bound labor was the only way that tobacco could be produced profitably this was overwhelmingly provided by indentured servants – usually English in the 1600s – rather than slaves.

Indentured servants are essentially temporary slaves. In exchange for passage across the ocean plus room and board they agree to serve as bound labor for a fixed period of time – seven years was common – during which time they could be bought, sold, and treated as things but after which they would be set free, given a reward (often land on the frontier), and allowed to join society as free citizens.

The first Africans in Virginia arrived in 1619 – a year before there were Pilgrims in New England, for those of you keeping score at home – and from what historians are able to tell they were treated as indentured servants as well – held in bondage, treated as things, and bought and sold like English indentured servants, but if they survived they were set free. There was in fact a small community of freed Africans in Virginia in the 1620s and 1630s, and they had the same rights as freed English indentured servants. They could own land and become tobacco planters. If they owned enough land they could vote and serve on juries – juries that were usually deciding the fates of white people, something that wouldn’t happen again in Virginia until the 1970s once the practice halted. They could marry who they chose, and even own indentured servants or slaves of their own.

This tells you that “race” as we understand the term didn’t mean a whole lot to the settlers. They were far more likely to care about religious views – there is a reason that Shakespeare’s Othello is described as the Moor (“the Muslim”) of Venice rather than the black man of Venice, after all.

That began to change in the 1640s, as “race” in the modern sense began to matter more to Virginians than it did in the decades prior. Historians are not exactly sure why this change happened but happen it did. You see laws passed discriminating between the rights of freed African indentured servants versus freed English indentured servants, denying freed Africans the right to serve in the militia or own a gun (gun ownership being a white privilege of long standing in this country). But slavery itself was still fairly uncommon and would remain so into the 1670s. In 1660 there were fewer than 1000 slaves in Virginia. In 1670 there were about 2000 – roughly 5% of the population. They were outnumbered by indentured servants three to one.

The reason for this is simple economics plus demographics. In the early 17th century few settlers, bound or free, survived seven years in Virginia. Slaves are expensive because you’re paying for a lifetime’s worth of labor, whereas indentured servants are far cheaper because you’re only paying for seven years’ worth of labor. And if both of them are likely to die before seven years is up, there’s no point in paying for a slave. You get all of the economic benefits of slavery without all the costs by going with indentured servants, and if you think it is immoral to reduce human beings to chattels this way you’re absolutely right. But that was the logic at the time. It wasn’t morality that kept slavery from being common. It was just finances.

But by the 1660s mortality rates had declined to the point where most indentured servants were surviving long enough to be set free. You’d think this was a good thing, and for the indentured servants it was, but it had consequences.

Those freed indentured servants would often be given land out in the back country, much to the dismay of the Native Americans who had already seen a large chunk of their land taken from them. This meant constant conflict between the settlers and the Natives, conflict that threatened to burst out into warfare at any time.

And having been tobacco field hands during their time in Virginia, those freed indentured servants would set about trying to make a living doing the one thing they knew how to do, which was grow more tobacco. Which means you had even more people growing a crop that was even less valuable, and you know what that means? It means they’re going to fail, that’s what it means.

So in the 1660s Virginia became divided into two hostile camps.

On the one hand you had the wealthy planter elites – the people who had made their money when tobacco prices where high and could now afford to branch out into other things like money lending or the fur trade. These people lived in the eastern tidewater areas and were the ones who controlled the Virginia government.

On the other hand, you had a growing number of small tobacco farmers out on the frontier – mostly freed indentured servants. These people were poor, powerless, and increasingly angry, particularly after the tidewater elite put strict property limits on their right to vote (voter suppression being an age-old tactic in the US) and refused to help them eradicate the local Native Americans, with whom the elites traded for their furs.

By the early 1670s Virginia was a society on the brink of disaster, and the guy who set things in motion was Nathaniel Bacon.

Bacon was 26 years old when he arrived in Virginia in 1674. Like many early Virginia settlers he was a gentleman – a social rank at the time, not simply a description of an adult male – and he was eager to rebuild the fortune he had squandered back in England. Governor William Berkeley was sufficiently impressed with the young man that he appointed Bacon to the governor’s council, but they very quickly fell out when Berkeley denied him a license to trade with the Natives.

Bacon then threw himself into the opposition – an opposition centered around the small tobacco planters of the back country – and became their leader.

After rising tensions turned to violence between the settlers and the Natives in 1675 and 1676 (largely because Bacon and the back countrymen worked on a “kill them all and let God sort them out” philosophy of deciding between allies and threats), Berkeley threw Bacon off the council entirely. Bacon then led the frontiersmen against the Virginia government, routed the colonial militia, and burned the capital, Jamestown, to the ground in the summer of 1676. Bacon then died of dysentery in October, after which Berkeley recaptured Jamestown, executed 23 of the surviving rebels, boarded a ship to explain the situation to the crown in 1677, and died before he could do so.

Given that I have just described the entire rebellion in a single paragraph of just over a hundred words – a rebellion which failed and left the original government in charge when all was said and done, it must be noted – it is a fair question at this point to ask how this could possibly be the most important event in American history.

The rebellion had consequences, that’s how.

When the tidewater elite looked back over the events of Bacon’s Rebellion, they asked themselves, “What was the main source of this revolt?” And the answer they came up with was obvious: the small tobacco planters out in the back country. Small planters who had once been indentured servants but had survived to earn their freedom and their land thanks to the declining mortality rates of 17th century Virginia. Bacon had led them, but they were the root of the problem and as long as there were indentured servants living long enough to be freed they would constitute a poor, angry, volatile underclass ready to be stirred up by an ambitious leader like Nathaniel Bacon.

But Virginia needed bound labor, because free labor wasn’t going to grow tobacco.

So the solution was clear: find a source of bound labor that they didn’t have to set free.

Slaves, in other words.

Slavery meant no dangerous class of poor, freed indentured servants to deal with, and thanks to the declining mortality rates and the fact that slavery was made inheritable through the mother (and think about the incentives in that little arrangement the next time someone tells you the free market is the engine of liberty, why don’t you) slavery was now not only cost effective but potentially profitable.

On top of that race-based chattel slavery created a bond between the eastern planter elite and the small western planters, one that would reduce future rebellions by keeping the two sides allied against a common enemy, because as long as you had race-based slavery whites would unite against blacks – even across political or economic lines, even at the expense of their own political or economic interests.

Convince poor whites that blacks or other non-whites are the enemy and they will slit their own throats every time. Go ahead and dispute that if you want. I dare you. Go ahead.

Bacon’s Rebellion is the single most important event in all of American history because more than any other event it sets the United States on the path toward race-based chattel slavery, toward dividing Americans into white and nonwhite, into people and things, and from that decision nearly all of the rest of American history flows.

By 1700 race-based chattel slavery is the default system of bound labor in the American colonies, particularly in the south. There were roughly nineteen thousand slaves in the Chesapeake region in 1700 – 22% of the population, more or less – which is a significant increase from 1670, and it would only continue to grow. By 1750 there were over 200,000 slaves in the thirteen colonies that would become the US. By 1775 that would be about half a million – again, roughly 20% of the population.

If you want to understand colonial society, you need to understand this. If you want to understand the Civil War, you need to understand this. If you want to understand pretty much any part of American history, you need to understand this.

If you want to understand the headlines today, you need to understand Bacon’s Rebellion and its consequences.

We’re living them now.

Tuesday, June 9, 2020

Notes from Lockdown

1. We’re in the middle of a tropical storm here in Wisconsin, in case you were wondering what level of apocalypse 2020 is at now.

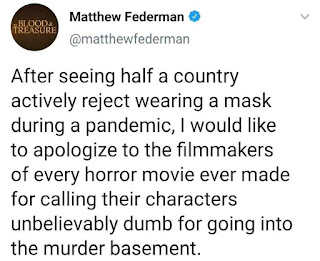

2. Am I the only one who remembers that there’s a pandemic going on or are there others? The news has been inundated with the ongoing protests – and, really, those protests are important so I’m not complaining about being inundated – but I suspect that we are going to be reminded of the coronavirus in a heavy-handed way in the very near future and I’m not looking forward to that.

3. We’re already seeing the spikes that came from the rush to open up for Memorial Day – most of the states that threw open their doors without preparations are worse than they were before they went into lockdown in the first place (hi there, Texas!). The end of June is going to be ugly – and not just from the transmissions from the demonstrations (though I see a lot of people wearing masks at those events and trying to keep their distance, which is good) but from all the other people who have simply moved on and forgotten. We are not a species built to last.

4. I’m impressed by the staying power of the protests. Those people are doing important things, often at great cost to themselves (hint to the police: in an age where every single person on the street has a camera in their pocket that can take high-quality video and send it worldwide with the press of a button, if people are protesting against being assaulted by the police it’s probably a good idea not to assault them, you think?), and what it’s astonishing how quickly the public conversation has turned in their favor. It’s almost as if those protesters were saying things that desperately needed to be said and advocating for things that the US had better start doing if it wants to survive.

5. I’ve been working on a larger post about the current situation that keeps getting sidetracked because to be honest it’s hard to focus these days. This may be a problem for the various academic things I’m getting paid to do this summer as well. But the world is stressful even for a privileged white guy like me, which makes the protesters that much more impressive when you think about it.

6. I always wear a mask if I’m out in public and expect to be around other people, for the same reason I wear a seatbelt. I spent five years as a firefighter on a rescue squad. As a group we devoted a disturbing number of hours to scraping people off the road from where they had skidded to a halt after being ejected from their cars or peeling them out of their windshields if they stayed inside, and it’s just a basic safety measure to buckle in. I have no patience for people who think their mild inconvenience is more important than the lives of those around them.

7. Of course, wearing a mask brings up three problems. First, I have a big head. Literally. Not sure about figuratively – I’m not the best person to ask, so you’ll have to enquire among those who deal with me every day as they’ll have a more objective viewpoint. But definitely literally. This means that the elastic straps on most masks tend to be just that much too short. Second and related, apparently I have flexible ears. I’m sure this is an evolutionary adaptation designed to help me squeeze through narrow corridors but it does mean that any elastic band taut enough to keep the mask from slipping off my face is just going to make it slide right off my head as my ears bend to make way for it. So Kim made me a couple of masks that tie instead, which helps. Third, I wear glasses and it’s like going out in a scarf in February every time I put the mask on. But I wear the mask anyway, because I am not stupid.

8. I’d say that mask compliance in most of the places I’ve been over the last two weeks (i.e. several different grocery stores, one hardware store, and a feed store to restock the chickens) has been between 50 and 70%. Could be better. Not as bad as I’d feared. A surprising number of people have figured out that pandemics don’t care about your politics and they’re just trying to get by. Oddly enough the feed store was the worst. The hardware store actually required masks and had people stationed at the front door to enforce it.

9. I finally finished the Big Box O’ Wine that I bought for quarantine back in March. What can I say? I have a drinking problem. I don’t drink nearly as much as I feel I ought to be doing these days.

10. I’m up to Sacre Bleu in my “read all the Christopher Moore books” project. Seriously, you need to be reading his stuff.

2. Am I the only one who remembers that there’s a pandemic going on or are there others? The news has been inundated with the ongoing protests – and, really, those protests are important so I’m not complaining about being inundated – but I suspect that we are going to be reminded of the coronavirus in a heavy-handed way in the very near future and I’m not looking forward to that.

3. We’re already seeing the spikes that came from the rush to open up for Memorial Day – most of the states that threw open their doors without preparations are worse than they were before they went into lockdown in the first place (hi there, Texas!). The end of June is going to be ugly – and not just from the transmissions from the demonstrations (though I see a lot of people wearing masks at those events and trying to keep their distance, which is good) but from all the other people who have simply moved on and forgotten. We are not a species built to last.

4. I’m impressed by the staying power of the protests. Those people are doing important things, often at great cost to themselves (hint to the police: in an age where every single person on the street has a camera in their pocket that can take high-quality video and send it worldwide with the press of a button, if people are protesting against being assaulted by the police it’s probably a good idea not to assault them, you think?), and what it’s astonishing how quickly the public conversation has turned in their favor. It’s almost as if those protesters were saying things that desperately needed to be said and advocating for things that the US had better start doing if it wants to survive.

5. I’ve been working on a larger post about the current situation that keeps getting sidetracked because to be honest it’s hard to focus these days. This may be a problem for the various academic things I’m getting paid to do this summer as well. But the world is stressful even for a privileged white guy like me, which makes the protesters that much more impressive when you think about it.

6. I always wear a mask if I’m out in public and expect to be around other people, for the same reason I wear a seatbelt. I spent five years as a firefighter on a rescue squad. As a group we devoted a disturbing number of hours to scraping people off the road from where they had skidded to a halt after being ejected from their cars or peeling them out of their windshields if they stayed inside, and it’s just a basic safety measure to buckle in. I have no patience for people who think their mild inconvenience is more important than the lives of those around them.

7. Of course, wearing a mask brings up three problems. First, I have a big head. Literally. Not sure about figuratively – I’m not the best person to ask, so you’ll have to enquire among those who deal with me every day as they’ll have a more objective viewpoint. But definitely literally. This means that the elastic straps on most masks tend to be just that much too short. Second and related, apparently I have flexible ears. I’m sure this is an evolutionary adaptation designed to help me squeeze through narrow corridors but it does mean that any elastic band taut enough to keep the mask from slipping off my face is just going to make it slide right off my head as my ears bend to make way for it. So Kim made me a couple of masks that tie instead, which helps. Third, I wear glasses and it’s like going out in a scarf in February every time I put the mask on. But I wear the mask anyway, because I am not stupid.

8. I’d say that mask compliance in most of the places I’ve been over the last two weeks (i.e. several different grocery stores, one hardware store, and a feed store to restock the chickens) has been between 50 and 70%. Could be better. Not as bad as I’d feared. A surprising number of people have figured out that pandemics don’t care about your politics and they’re just trying to get by. Oddly enough the feed store was the worst. The hardware store actually required masks and had people stationed at the front door to enforce it.

9. I finally finished the Big Box O’ Wine that I bought for quarantine back in March. What can I say? I have a drinking problem. I don’t drink nearly as much as I feel I ought to be doing these days.

10. I’m up to Sacre Bleu in my “read all the Christopher Moore books” project. Seriously, you need to be reading his stuff.

Monday, June 8, 2020

Memes on the Current Situation

I've been working on a longer post on current events, but since I also seem to be collecting a pile of memes worth sharing, I figured I'd send them out into the world too.

--

--

Wednesday, June 3, 2020

Bonus

In 1924, Congress authorized a bonus of up to $500 for American veterans of World War I, with additional sums up to a total of $625 depending on how long they served overseas. This was a lot of money at the time and was meant to compensate those soldiers for lost wages during their service.

The money would not be paid out until 1945, which wasn’t too much of a problem for most of the veterans at the time. The 1920s were a decade of superficial but real prosperity – a decade not unlike our own, with wide and worsening inequalities of wealth and deteriorating conditions for the poor, but with a small but steady growth of the middle class and a general sense that even if you weren’t currently part of it this prosperity might eventually trickle down to you. In many ways this sense of optimism was an illusion – vast sectors of the economy were left out of this prosperity, including agriculture, textiles and coal mining – but sometimes illusions are enough.

And then in 1929 the bottom fell out of the economy with the onset of the Great Depression.

The banking system collapsed. The GDP fell by nearly half, from $103 billion in 1929 to $58 billion in 1932. Private investment dropped by 88% over that time frame. Construction dropped by 78%. Corporate profits fell by 90%. Exports and imports fell by nearly 70%. Farm income – already precariously low – dropped by 60% between 1929 and 1932. At one point in 1932 one quarter of all the land in Mississippi was up for foreclosure sale.

Unemployment, meanwhile, skyrocketed. Unemployment stood at 3.2% in 1929 – a deceptively low figure given the extreme volatility of the job market in the laissez-faire 1920s when job security was pretty much nonexistent for most people, but manageably small nonetheless. By 1932 it was 20%. By 1933 it was 25%. And those numbers are almost certainly low, given the crude statistics of the day. In the cities it was higher – closer to 50% in industrial centers such as Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. Nearly 80% in Toledo. Unemployment would average 20% for the rest of the 1930s and never dropped below 15% during the entire decade.

Herbert Hoover had no idea how to handle this.

Hoover was not a hard-hearted man, despite his later reputation. His nickname, in fact, was The Great Humanitarian – something he earned by being instrumental in the relief efforts that kept much of Europe from starving in the immediate aftermath of WWI.

But he was a prisoner of his ideology and he firmly believed that the responsibility for recovering from the Great Depression, as it was being called by then, lay entirely in the hands of individuals, private charities, corporations, and local governments, and should be implemented according to supply-side economics – wealth transferred to the rich in the hopes that enough of it would trickle down to everyone else to solve the problem. This is a favorite tactic of the right wing even today, and immensely popular among those who are already rich and powerful, for obvious reasons.

The problem, though, is that supply side economics doesn’t work in a demand side economy. Never has. Never will. It’s not complicated, people. It’s just math. Politicians may lie but the numbers don’t, and you can crunch the numbers any way you want but you’ll never get to a place where they tell you anything else unless you lie, which gets us back to the beginning of this sentence fairly quickly.

The US shifted over from a producer (supply side) economy to a consumer (demand side) economy in the 1920s and has never shifted back and the things you do to fix a producer economy are exactly the things that will intensify a crisis in a consumer economy, which made Hoover’s efforts to respond to the Depression ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Individuals, private charities, corporations, and local governments were completely overwhelmed by the scale of the crisis and could provide little help. And things got worse.

Americans literally starved in the streets even as unsellable crops were plowed under.

When Hoover proved willing to bail out big business and the rich in the name of supply side economics but remained adamant in refusing to help the vast majority of Americans directly, the Depression became personal. It became the Hoover Depression. Tar-paper shacks occupied by the homeless unemployed became Hoovervilles. Old newspapers used to keep warm became Hoover blankets. Jackrabbits became Hoover hogs. The mood got ugly.

And into this came the Bonus Army.

In May 1932 some 400 World War I veterans under the leadership of Walter Waters gathered in Portland Oregon and began the long journey to Washington DC. Their goal, in the middle of the worst economic collapse in the American history, was to convince the government to pay out the bonuses now, when they needed them, rather than wait until 1945 when they might well be dead.

As Harry Hopkins, one of the leaders of the later New Deal, put it, “People don’t eat in the long run. They eat every day.”

Waters and his supporters rode out on a freight train that had been loaned to them by supportive railroad leaders, and when the train stopped in Iowa they got out and continued on their journey, hitchhiking and walking. By June 1 when they reached the capital there were about 1500 men in the Bonus Army (or Bonus Expeditionary Force, a play on the American Expeditionary Force that had gone overseas to fight WWI) as it was now called. They set up a number of camps – a few in abandoned buildings within the city itself, and the largest on some swampy private land outside of the city known as Anacostia Flats. The camps were well regulated, as you would imagine camps run by military veterans would be, and the veterans worked with the sympathetic head of the Washington DC police – a WWI veteran named Pelham Glassford – to maintain order. Waters and the Bonus Army staged daily demonstrations and peaceful marches in front of the Capitol, but Hoover never bothered to talk with them. Meanwhile more veterans and their families continued to pour into the city, until eventually there were nearly 20,000 people in the various camps.

In mid-June the House of Representatives voted to pay them their bonus, but Hoover promised to veto the bill if it came to him and the Senate rejected it. Defeated, many of the Bonus Army members left the capital, but thousands stayed. It was the Depression. Many had lost their homes. They had nowhere else to go.

Things came to a head in July. Secretary of War Patrick Hurley ordered the police to clear the city of the Bonus Army – in part because they were a continuing embarrassment and in part because the buildings they occupied were scheduled to be demolished to make way for new government offices. The confrontation turned violent despite the previous good relations between the Bonus Army and the local police, and in the melee that followed two veterans were killed.

At that point the President called out the Army and ordered it into action against American citizens on American soil.

To deal with the civilians in his midst, General Douglas MacArthur assembled a force of over a thousand infantry backed by a detachment of mounted cavalry and six tanks and, with his subordinates – Major Dwight D. Eisenhower and Major George S. Patton – and marched on the camps in the city itself. Using tear gas and bayonets, MacArthur’s forces cleared the buildings. At this point Hoover ordered the mission halted.

MacArthur, however – in what would become a signature characteristic of his military career – decided to exceed his authority.

Despite being twice ordered by Hoover not to cross the bridge into Anacostia Flats, MacArthur sent his forces to clear the camp there by force. In the ensuing panic over a hundred veterans were injured and an infant was killed. MacArthur then ordered the encampment burned. All of this was captured in photographs and newsreel film and shown to a horrified American public.

Rather than condemn MacArthur for his insubordination, Hoover mounted a vigorous defense of his actions. It did him no good. The spectacle of American military forces firing on civilians – veterans and their families, no less – effectively destroyed Hoover in the public eye.

“I voted for Herbert Hoover in 1928,” said one woman. “God forgive me and keep me alive at least till the polls open next November!” On a campaign stop in Detroit later in 1932, Hoover was greeted with shouts of “Down with Hoover! Slayer of veterans!”

He was destroyed in the 1932 election, and his party lost control of every branch of the government for the next decade.

We are rapidly reaching our Bonus Army moment here in 2020. The current president is threatening to use military force against civilians, most of whom are peacefully protesting as is their right under the First Amendment. The protests have been infiltrated by right-wing extremists bent on causing havoc, and he’s playing right into their hands. He’s declared that antifascists are the enemy (which raises an interesting question as to what he considers himself and his supporters to be) and he is demanding blood.

It didn’t end well last time.

It won’t end well this time.

Unless you’ve studied the Depression in some detail you probably don’t realize how close to revolution this country came during that time. That’s what happens when you take people with legitimate grievances and treat them like enemies. We’ve reached the point where there are CIA agents openly describing der Sturmtrumper’s attempt to crush these protests as evidence of a failed state ready to collapse. They’ve seen it happen elsewhere. It can happen here. It is happening here.

Franklin Roosevelt learned his lesson from the Bonus Army. He didn’t want to pay them their bonus any more than Hoover did, but when a smaller second round of Bonus Army marchers showed up a couple of years later he didn’t send out the army. He sent out his wife to talk to them, and he sent out food. There was no violence, and Congress eventually passed a bonus payout over his veto and he was smart enough to accept it and let the matter drop.

If we’re lucky we’ll get to a new administration that will learn the lessons of the past sometime soon, one that will work to restore the damage done to the American republic over the last three years.

If we’re not, well, hang onto your hats folks. We could end up miles from here.

The money would not be paid out until 1945, which wasn’t too much of a problem for most of the veterans at the time. The 1920s were a decade of superficial but real prosperity – a decade not unlike our own, with wide and worsening inequalities of wealth and deteriorating conditions for the poor, but with a small but steady growth of the middle class and a general sense that even if you weren’t currently part of it this prosperity might eventually trickle down to you. In many ways this sense of optimism was an illusion – vast sectors of the economy were left out of this prosperity, including agriculture, textiles and coal mining – but sometimes illusions are enough.

And then in 1929 the bottom fell out of the economy with the onset of the Great Depression.

The banking system collapsed. The GDP fell by nearly half, from $103 billion in 1929 to $58 billion in 1932. Private investment dropped by 88% over that time frame. Construction dropped by 78%. Corporate profits fell by 90%. Exports and imports fell by nearly 70%. Farm income – already precariously low – dropped by 60% between 1929 and 1932. At one point in 1932 one quarter of all the land in Mississippi was up for foreclosure sale.

Unemployment, meanwhile, skyrocketed. Unemployment stood at 3.2% in 1929 – a deceptively low figure given the extreme volatility of the job market in the laissez-faire 1920s when job security was pretty much nonexistent for most people, but manageably small nonetheless. By 1932 it was 20%. By 1933 it was 25%. And those numbers are almost certainly low, given the crude statistics of the day. In the cities it was higher – closer to 50% in industrial centers such as Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. Nearly 80% in Toledo. Unemployment would average 20% for the rest of the 1930s and never dropped below 15% during the entire decade.

Herbert Hoover had no idea how to handle this.

Hoover was not a hard-hearted man, despite his later reputation. His nickname, in fact, was The Great Humanitarian – something he earned by being instrumental in the relief efforts that kept much of Europe from starving in the immediate aftermath of WWI.

But he was a prisoner of his ideology and he firmly believed that the responsibility for recovering from the Great Depression, as it was being called by then, lay entirely in the hands of individuals, private charities, corporations, and local governments, and should be implemented according to supply-side economics – wealth transferred to the rich in the hopes that enough of it would trickle down to everyone else to solve the problem. This is a favorite tactic of the right wing even today, and immensely popular among those who are already rich and powerful, for obvious reasons.

The problem, though, is that supply side economics doesn’t work in a demand side economy. Never has. Never will. It’s not complicated, people. It’s just math. Politicians may lie but the numbers don’t, and you can crunch the numbers any way you want but you’ll never get to a place where they tell you anything else unless you lie, which gets us back to the beginning of this sentence fairly quickly.

The US shifted over from a producer (supply side) economy to a consumer (demand side) economy in the 1920s and has never shifted back and the things you do to fix a producer economy are exactly the things that will intensify a crisis in a consumer economy, which made Hoover’s efforts to respond to the Depression ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Individuals, private charities, corporations, and local governments were completely overwhelmed by the scale of the crisis and could provide little help. And things got worse.

Americans literally starved in the streets even as unsellable crops were plowed under.

When Hoover proved willing to bail out big business and the rich in the name of supply side economics but remained adamant in refusing to help the vast majority of Americans directly, the Depression became personal. It became the Hoover Depression. Tar-paper shacks occupied by the homeless unemployed became Hoovervilles. Old newspapers used to keep warm became Hoover blankets. Jackrabbits became Hoover hogs. The mood got ugly.

And into this came the Bonus Army.

In May 1932 some 400 World War I veterans under the leadership of Walter Waters gathered in Portland Oregon and began the long journey to Washington DC. Their goal, in the middle of the worst economic collapse in the American history, was to convince the government to pay out the bonuses now, when they needed them, rather than wait until 1945 when they might well be dead.

As Harry Hopkins, one of the leaders of the later New Deal, put it, “People don’t eat in the long run. They eat every day.”

Waters and his supporters rode out on a freight train that had been loaned to them by supportive railroad leaders, and when the train stopped in Iowa they got out and continued on their journey, hitchhiking and walking. By June 1 when they reached the capital there were about 1500 men in the Bonus Army (or Bonus Expeditionary Force, a play on the American Expeditionary Force that had gone overseas to fight WWI) as it was now called. They set up a number of camps – a few in abandoned buildings within the city itself, and the largest on some swampy private land outside of the city known as Anacostia Flats. The camps were well regulated, as you would imagine camps run by military veterans would be, and the veterans worked with the sympathetic head of the Washington DC police – a WWI veteran named Pelham Glassford – to maintain order. Waters and the Bonus Army staged daily demonstrations and peaceful marches in front of the Capitol, but Hoover never bothered to talk with them. Meanwhile more veterans and their families continued to pour into the city, until eventually there were nearly 20,000 people in the various camps.

In mid-June the House of Representatives voted to pay them their bonus, but Hoover promised to veto the bill if it came to him and the Senate rejected it. Defeated, many of the Bonus Army members left the capital, but thousands stayed. It was the Depression. Many had lost their homes. They had nowhere else to go.

Things came to a head in July. Secretary of War Patrick Hurley ordered the police to clear the city of the Bonus Army – in part because they were a continuing embarrassment and in part because the buildings they occupied were scheduled to be demolished to make way for new government offices. The confrontation turned violent despite the previous good relations between the Bonus Army and the local police, and in the melee that followed two veterans were killed.

At that point the President called out the Army and ordered it into action against American citizens on American soil.

To deal with the civilians in his midst, General Douglas MacArthur assembled a force of over a thousand infantry backed by a detachment of mounted cavalry and six tanks and, with his subordinates – Major Dwight D. Eisenhower and Major George S. Patton – and marched on the camps in the city itself. Using tear gas and bayonets, MacArthur’s forces cleared the buildings. At this point Hoover ordered the mission halted.

MacArthur, however – in what would become a signature characteristic of his military career – decided to exceed his authority.

Despite being twice ordered by Hoover not to cross the bridge into Anacostia Flats, MacArthur sent his forces to clear the camp there by force. In the ensuing panic over a hundred veterans were injured and an infant was killed. MacArthur then ordered the encampment burned. All of this was captured in photographs and newsreel film and shown to a horrified American public.

Rather than condemn MacArthur for his insubordination, Hoover mounted a vigorous defense of his actions. It did him no good. The spectacle of American military forces firing on civilians – veterans and their families, no less – effectively destroyed Hoover in the public eye.

“I voted for Herbert Hoover in 1928,” said one woman. “God forgive me and keep me alive at least till the polls open next November!” On a campaign stop in Detroit later in 1932, Hoover was greeted with shouts of “Down with Hoover! Slayer of veterans!”

He was destroyed in the 1932 election, and his party lost control of every branch of the government for the next decade.

We are rapidly reaching our Bonus Army moment here in 2020. The current president is threatening to use military force against civilians, most of whom are peacefully protesting as is their right under the First Amendment. The protests have been infiltrated by right-wing extremists bent on causing havoc, and he’s playing right into their hands. He’s declared that antifascists are the enemy (which raises an interesting question as to what he considers himself and his supporters to be) and he is demanding blood.

It didn’t end well last time.

It won’t end well this time.

Unless you’ve studied the Depression in some detail you probably don’t realize how close to revolution this country came during that time. That’s what happens when you take people with legitimate grievances and treat them like enemies. We’ve reached the point where there are CIA agents openly describing der Sturmtrumper’s attempt to crush these protests as evidence of a failed state ready to collapse. They’ve seen it happen elsewhere. It can happen here. It is happening here.

Franklin Roosevelt learned his lesson from the Bonus Army. He didn’t want to pay them their bonus any more than Hoover did, but when a smaller second round of Bonus Army marchers showed up a couple of years later he didn’t send out the army. He sent out his wife to talk to them, and he sent out food. There was no violence, and Congress eventually passed a bonus payout over his veto and he was smart enough to accept it and let the matter drop.

If we’re lucky we’ll get to a new administration that will learn the lessons of the past sometime soon, one that will work to restore the damage done to the American republic over the last three years.

If we’re not, well, hang onto your hats folks. We could end up miles from here.

Monday, June 1, 2020

As If On Cue

It can happen here.

It is happening here.

Just today, as if on cue, in response to the protests that have erupted across the nation – protests against the slaughter of the innocent, protests that have been hijacked by violent right-wing extremists for their own malicious ends – der Sturmtrumper threatened to use military force against civilians within the borders of the United States.

He doesn’t have that power – not unless he is asked by the governor of whatever state in which he plans to use armed force – but that has never stopped a Fascist before. He will claim that power and he will use it.

This is textbook dictatorship.

First you create a situation so dire that people get angry. Then you inflame that and make it worse. Then you call out the army and declare yourself God Emperor of Shitsylvania, savior of all that is true and holy. At first people see it as calming. Then it descends into brutality and subjection, and good luck with getting rid of that. Ask half the nations of Latin America how that worked out for them and whether they think we should start down that path too.

It can happen here.

It is happening here.

This should not come as a surprise to anyone. Der Sturmtrumper and his minions have been baying for this since 2016 and they understand that this is their last chance. They cannot win in November. They cannot maintain their grip on power in a free and open republic. They cannot rule a democracy.

“When Fascism comes to America,” said Sinclair Lewis, “it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.” It’s almost as if Lewis had been watching today’s news reports, as der Sturmtrumper stood in front a church, waving a Bible, wearing his flag pin, calling for the end of the republic.

The bunker-dwelling coward in the Oval Office makes his demands, and the dregs of American society respond with arson, gunfire, and death.

My fellow Americans, we either stand in defense of the republic, the Constitution, and the freedoms we’re promised (and which, as Americans, we need to work to make real for all of us), or it all goes away sooner than you'd think possible.

It can happen here.

It is happening here.

Don’t say you weren’t warned.

It is happening here.

Just today, as if on cue, in response to the protests that have erupted across the nation – protests against the slaughter of the innocent, protests that have been hijacked by violent right-wing extremists for their own malicious ends – der Sturmtrumper threatened to use military force against civilians within the borders of the United States.

He doesn’t have that power – not unless he is asked by the governor of whatever state in which he plans to use armed force – but that has never stopped a Fascist before. He will claim that power and he will use it.

This is textbook dictatorship.

First you create a situation so dire that people get angry. Then you inflame that and make it worse. Then you call out the army and declare yourself God Emperor of Shitsylvania, savior of all that is true and holy. At first people see it as calming. Then it descends into brutality and subjection, and good luck with getting rid of that. Ask half the nations of Latin America how that worked out for them and whether they think we should start down that path too.

It can happen here.

It is happening here.